Indiana: Poverty Calculation Isn’t Accurate

Traditional poverty calculation doesn’t capture all of Indiana’s struggling families

A new report finds that poverty, or inadequate income to meet a household’s basic needs, is much higher and more extensive in Indiana than official counts suggest — particularly among working, single mothers of color.

The Overlooked and Undercounted report commissioned by the Indiana Community Action Poverty Institute analyzed how wages failed to keep pace even as family expenses increased – namely food, shelter, health care, transportation, and child care costs.

However, federal and state governments continue to use a measure that defines poverty based on one cost alone – food – and don’t account for increases in other categories.

Researchers with the Center for Women’s Welfare, part of the University of Washington School of Social Work, used the Self-Sufficiency Standard to identify 479,913 households that lack the income to meet their basic needs, far more than the 190,313 counted under the federal standard. The vast majority of families, 85%, had at least one worker whose wages didn’t meet the needs of their households.

“Using the official poverty thresholds results in more than 60% of these Indiana households being overlooked and undercounted, not officially poor yet without enough resources to cover their basic needs,” the report concluded.

The economic uncertainty of COVID-19 exacerbated many of these problems, though the expansion of certain programs like the Child Tax Credit likely mitigated some of that distress.

The Self-Sufficiency Standard vs. the official poverty level

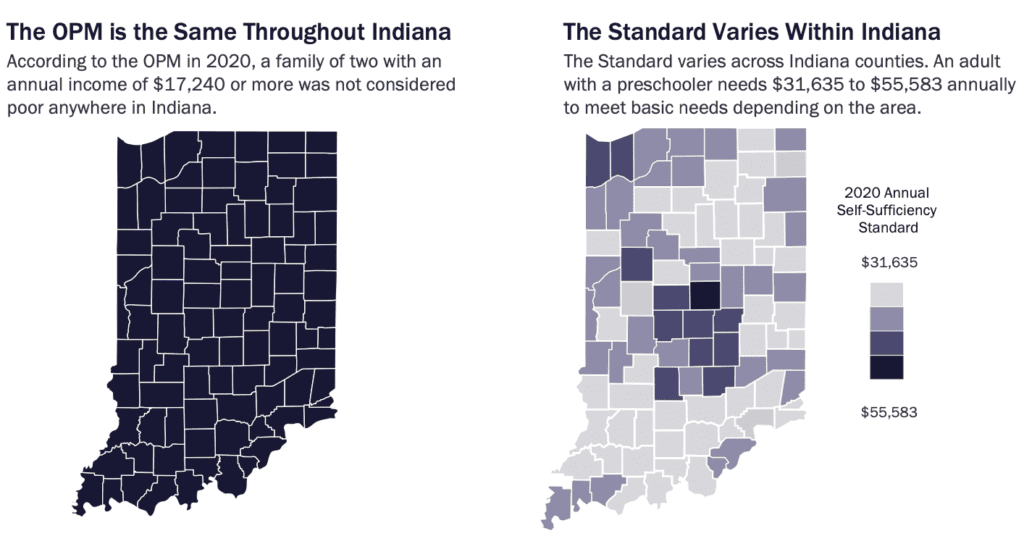

The report used the Self-Sufficiency Standard rather than the official poverty level because the former accounts for geographical location and family composition – which researchers argued made it a more accurate measure of poverty.

The official poverty measure (OPM) is the U.S. Census Bureau’s method of measuring poverty and differs from the federal poverty levels determined by Health and Human Services, which measures eligibility for anti-poverty programs. The traditional standard for measuring poverty is the same for every county in Indiana while the Self-Sufficiency Standard varies.

The Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison notes that the official poverty level relies on minimum food costs from 1963, adjusted for inflation when food purchases made up one-third of an average household’s budget. The number is the same across the country and counts all children equally – even though costs for children under 6 are significantly higher than for older children.

The Self-Sufficiency Standard doesn’t set food – over any other budget line item – as a set percentage and adjusts different categories based on current expenses.

Researchers drew from the data obtained from the American Community Survey between 2016 and 2020, excluding Hoosiers over the age of 65 and those with work-limiting disabilities even if they were part of another household.

Just over one in ten, 11%, of working-age households in Indiana fall under the official poverty measure, while 27% have an income below the self-sufficiency standard.

“We find that Indiana families struggling to make ends meet are neither a small nor a marginal group, but rather represent a substantial proportion of households in the state,” the report said. “With more than one in four Indiana households lacking enough income to meet their basic needs, the problem of economic insecurity even before the pandemic is extensive…”

The gap between the number of households counted under the self-sufficiency standard and the official poverty level constituted a group that was “overlooked and undercounted” when analyzing poverty rates and their impact. These Hoosiers were most likely left behind and left out of anti-poverty programming.

Hoosiers of color most likely to be impoverished

“Not only do governmental poverty statistics underestimate the number of households struggling to make ends meet, but the underestimation creates broadly held misunderstandings about who is in need,” the report said. “These misapprehensions harm our ability to respond to the changing realities facing low-income families.”

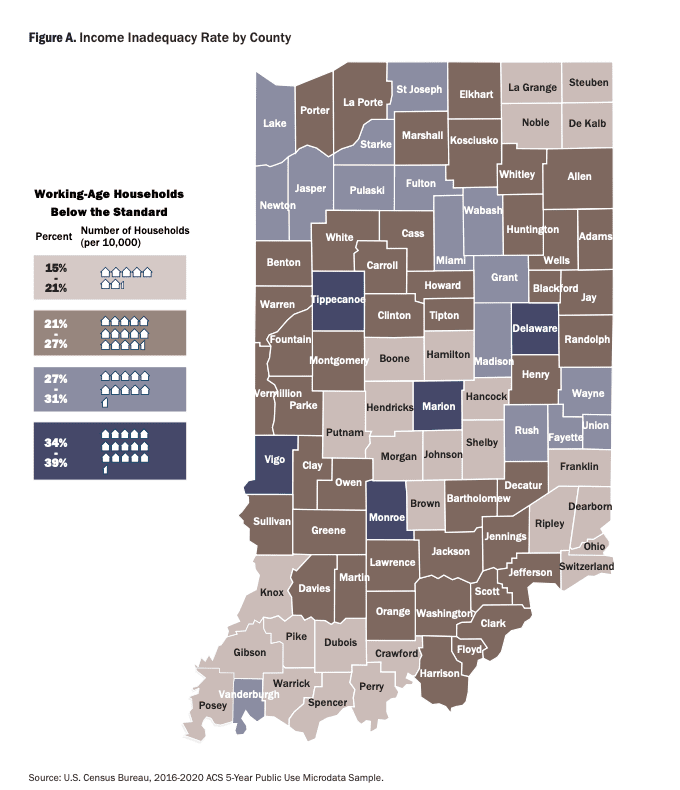

Nearly one-third of Hoosier households whose income didn’t match their needs came from just five counties: Vigo, Tippecanoe, Marion, Monroe, and Delaware.

The report noted that those five counties all housed the state’s largest colleges. Removing college-attending households made the insufficiency rate drop by 7% on average – with just a 1% impact in Marion County and a 11%-12% impact on Tippecanoe and Monroe.

Regardless of whether they resided in an urban or a rural county, single mothers struggled to pay their bills more than their male counterparts. Over half of single women living with children were more likely to have an inadequate income, up to 72% of mothers in some parts of the state. Income inadequacy varied by county and counties with the biggest college populations fared worse than their peers.

Hoosiers of color were disproportionately more likely to struggle with economic insecurity and foreign-born residents. Nearly half of Black households, 48%, and Latinx/Hispanic households, 45%, didn’t make enough money compared to just 22% of white households.

Poverty rates for American Indian households, 39%, and Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander households, 32%, were also higher than white Hoosiers.

Over half, 51%, of all residents who aren’t citizens fall under the defined poverty guidelines. Only 3% of Hoosier households are led by a non-citizen but those households account for 8% of all households below the sufficiency standard.

Education didn’t make a difference regarding race, with Black women-led households falling behind those led by white men, with “women of color in Indiana… more than twice as likely to have inadequate income compared to White men with the same education levels.”

Generally, households with higher education attainment were less likely to have a budget deficit, with over half, 54%, of those without a high school diploma having inadequate income.

Impact on children, employment

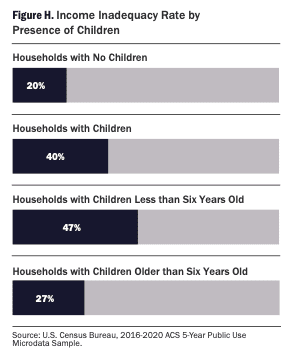

Households with children ranked 16 percentage points higher in terms of income inadequacy than households without children. Over one-third of families with children, 36%, fell into this category and the number increased to 47% when the children were under 6.

“While households with children only account for 41% of all households in Indiana, over 55% of households with incomes below the Standard have children present,” the report said.

Any combination of these factors – race or ethnicity, citizenship, women-led households or children under the age of 6 – made those households even less likely to have sufficient income. Income inadequacy increased as families had children, especially for families with children too young to attend school.

“Single mother of color-led households were about nine times more likely to be struggling to make ends meet than White married-couple households without children, increasing to nearly ten times more likely if the children were young,” the report said. “With child care closures, remote learning and disruptions in the labor market, the COVID-19 pandemic placed new pressures on already struggling single mothers, especially single mothers of color.”

Not even full-time employment was enough to keep some families afloat. Hoosier families of color were still more likely to have insufficient income when with two full-time workers in the house when compared to white Hoosiers, 28% and 13%, respectively. Researchers attributed this to the “racial wage gap,” with households of color making just 80% of the median earnings of white households, or $16.03 versus $20.00 per hour.

In Indiana, the median hourly wage for women is $16.83 compared to $21.63 for men.

The most frequent occupation for those living below the sufficiency standard was a cashier, accounting for 4% of all workers heading households. Other common occupations included: restaurant employees, nursing assistants, retail, personal care aides, construction workers, housekeepers, receptionists and postsecondary teachers.

“This data highlights that workers in Indiana will not benefit from returning to just any job,” the report concluded. “This post-pandemic labor market needs improved opportunities in positions that provide a family-sustaining wage.”

Indiana Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Indiana Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Niki Kelly for questions: info@indianacapitalchronicle.com. Follow Indiana Capital Chronicle on Facebook and Twitter.