Now Is A Good Time To Activate Your Vagus Nerve

Four simple steps to return to a ‘rest and digest’ state

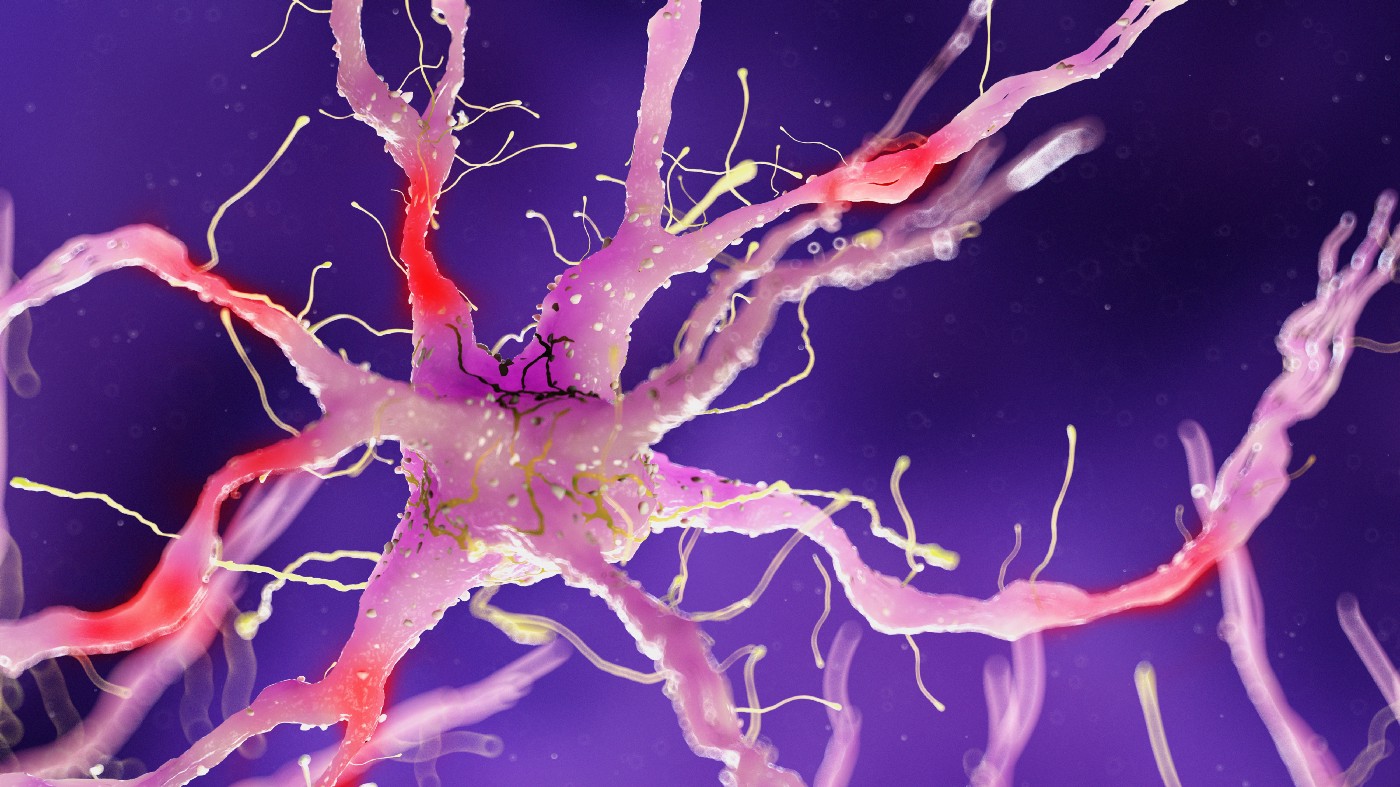

If you experience a racing heartbeat or tightness in your chest when you read a news story about the pandemic, it’s because of your vagus nerve or sympathetic nervous system. When the brain senses a threat, it triggers the fight-or-flight response.

On the flip side, your parasympathetic nervous system plays a role in calming your body, and for example, escaping from a grizzly bear and returning to your safe, cozy cave signals to the brain that the threat is gone so the stress response ends. Now that you’ve resolved the danger, you can return to a state of peace.

But what happens when a stressor doesn’t have a definitive ending — like, say, a pandemic that might go on for months? You could suffer some significant health consequences — unless you intervene with the help of your nervous system.

Emerging research on the vagus nerve, a major nerve in the parasympathetic nervous system, sheds light on how people tune in to their nervous systems and find ways back to a “rest and digest” state amidst chronic stress.

In his “polyvagal theory,” professor of psychiatry Stephen Porges hypothesizes that the parasympathetic nervous system has two parts that cause two different responses: the dorsal vagal nerve network and the ventral vagal nerve network.

When you can’t resolve a threat through fight-or-flight (you can’t exactly run away from or physically fight a virus) or establish a social connection to help calm you, your body sometimes decides it’s better to physically and mentally “check out.” That’s called dissociation, and it’s the work of the dorsal vagal nerve network. When you’re dissociated, you’ll feel powerless and hopeless, or even depressed — that’s one reason it’s so easy to glue yourself to the couch and go numb after you hear news about the virus.

The ventral vagal nerve network, on the other hand, gets activated when you’re connecting with another person (or with yourself, by responding to your body’s signs of stress), which triggers calmness. So this is the part of your nervous system you want to stimulate when you’re stressed.

Also known as the social engagement system, the ventral vagal network runs upward from the diaphragm area to the brain stem, crossing over nerves in the lungs, neck, throat, and eyes. Actions involving these body parts — including deep breaths, gargling, humming, or even social cues like smiling or making eye contact with someone — send messages to the brain that it’s okay to relax.

Through the ventral vagal network, you can limit the effects of stress and prevent dissociation. Here’s a four-step plan to activate it — and regain a sense of calm — when the threat of Covid-19 is overwhelming you.

Tune into how your body feels

If you’re not aware of how your body feels when you’re stressed, it’s hard to know when you need to give your nervous system some relaxation. The first step back to “rest and digest,” Kolber says, is paying attention to your body’s sensations.

Lynn Bufka, Ph.D., senior director of practice research and policy at the American Psychological Association (APA), recommends noting your body’s baseline physical state when you’re calm so you can notice how stress changes your body. For example, go for a walk, stretch your legs, or even bend over and touch your toes, seeing what feels good and what doesn’t. “The more we recognize our bodies’ capabilities and limitations, the more we can take care of them,” she says.

Once you have a general understanding of your body’s “baseline,” you can notice the small ways stress impacts you physically. For example, you might feel your shoulders slightly tense when you read the news about the latest case numbers. Then, you can take time to relax them — an act of compassionate self-care that not only relieves physical pain but signals to your ventral vagus nerve you’re in a safe place.

Use your breath

Whether your sympathetic or dorsal nerves are active, mindful breathing — or paying focused attention to your breath — can be a powerful way to self-regulate. Specifically, deep breathing directly stimulates the ventral vagal system since the vagus nerve passes through the vocal cords.

Research shows that mindful, deep breathing from the diaphragm reduces cortisol, the stress hormone. For example, in a 2017 study, people who participated in a guided breathing program — where they took, on average, four deep breaths a minute — had lower cortisol levels in their saliva immediately after the exercise.

Boston-based therapist Kimberly Schmidt Bevans says the exhale is one of the most important aspects of mindful breathing. Exhaling longer than you inhale puts the ventral vagal network into action and promotes the rest and digest response.

Connect with people

Social connection, whether with other people or through what Kolber calls “compassionate attention” to yourself, is one of the most fundamental ways to activate the ventral vagal network. You can’t go out with friends because of practicing social distancing, but you can FaceTime a loved one or have a meaningful conversation with someone you’re isolating with. Lanius says establishing a sense of safety and connection with someone — and making eye contact, even over a Zoom meeting — can cue your body to relax.

Harness anxious thoughts

The story you tell yourself about your stressors can dictate how your body responds.

“How you interpret your situation, and its danger lays out the potential for how chronic your stress will be,” says Bufka. If you know external stressors aren’t changing anytime soon, it’s essential to minimize your perception of the threat by shifting how you respond mentally.

For instance, rather than thinking about social distancing as being stuck in your house indefinitely, think about being home as a way to contribute to public health and an opportunity to slow down.

Lanius says steering your thoughts in a more promising direction could cause the brain to send messages through the vagus nerve, triggering calm in all the organs and systems along the way.

One way to do that is by using your five senses. For example, going outside, listening to birds, and smelling a flower are all simple grounding activities that could help activate the ventral vagus nerve. Essentially, these things bring your body back to the present moment, which may feel safer to your nervous system than the potential scenarios of the future.

When you’re paying attention to both your mind and body under stress, you’ll feel more relaxed — and ultimately, more yourself. When you’re in the hyped-up state of perceiving everything as a threat, all your resources will try to hold it together. Try to cope with your emotional response, so you’ll have more energy and resources to problem-solve.