Europe’s Far-Right Lurch

The struggle to save democracy is proving even more difficult in Europe than in the US. Virtually every European country is bedeviled by the rising conflict between traditional political parties on one side and far-right, sometimes neo-fascist parties on the other.

Each such conflict has its own history and evolution. Still, they reveal a disturbing pattern not all that different from the Trump-fueled assault on democratic institutions and values we are experiencing. In a few words, the pattern is conspiracy-mongering, denigration of “the other,” appeals to white Christian nationalism, a focus on economic instability, and above all, constant outrage over social media—all with violence as an unspoken remedy.

In fact, according to one foreign-policy expert with whom I once worked (Morton Halperin), “murder is the best option” for autocrats. “Passive resistance works unless you have a leader who is willing to shoot people marching in the street.”

From Italy to Poland and (Yes) Sweden

Take Italy, for example, where a far-right candidate (Giorgia Meloni) is about to become prime minister. Her party, the Fratelli di Italia (Brothers of Italy), has ties to the Fascists of Mussolini’s day. She is the product of years of campaigning by Matteo Salvini’s League against a migrant “invasion,” the theft of Italians’ values, and the capture of Italy’s economy by “world elites”—meaning the forces of globalization.

Meloni was able to “ride a populist wave of anger as her political party strategically positioned itself as the opposition to the unfolding Neoliberal disaster that has set the Italian and European economy back decades.” Meloni’s party comes to power with only 25 percent support, but in combination with other parties, including Salvini’s League, it will hold the balance of power in parliament.

Or take Viktor Orbán’s Hungary: He has become the darling of the American far right, a bully in the best Trump tradition. Orbán makes no secret of his “illiberal” politics, which translates to undermining the institutions of democratic governance—the press, courts, and civil society–in the pursuit of lasting power. Here too, appeals to nativism have greatly helped his cause. And despite efforts by the EU to hold Orbán to account for violating its democratic rules, Orbán has shown no signs of adapting.

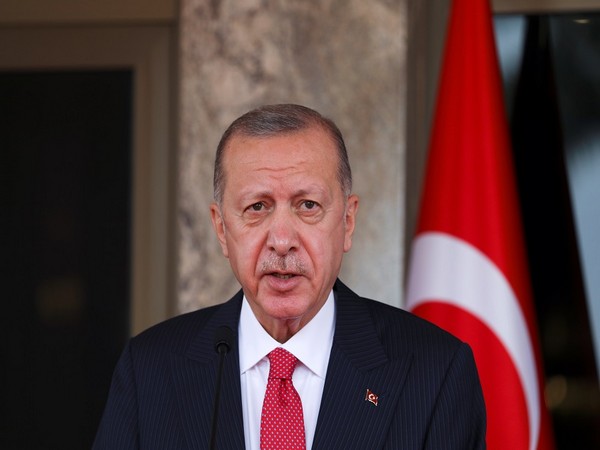

In Turkey, where another authoritarian leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has quashed criticism and tightened control over all independent sources of authority. His latest move is a law that will imprison anyone who “disseminates untrue information concerning the internal and external security, public order and public health of the country with the sole intention of creating anxiety, fear or panic among the public . . .”

Erdogan’s game is to keep democratic Europe at bay by demonstrating Turkey’s importance as a go-between with Putin. Meantime, Erdogan pursues his longstanding ambition to eradicate the pro-independence Kurdish Workers Party (PKK), which both Turkey and the US consider a terrorist organization. Although the PKK engages in violence, it has little choice given Erdogan’s relentless attacks on Kurdish forces in Syria, to which US and NATO have turned a blind eye.

Looking around the rest of Europe leaves little ground for optimism. Britain’s economic slide has come on the heels of a right-wing-supported Brexit that conservative leaders refuse to reverse.

In France, Emmanuel Macron defeated Marine Le Pen for the presidency by a healthy margin—58 percent to 42 percent—but (as one French source put it) “Le Pen’s result also marks the closest the far-right has ever come to taking power in France and has revealed a deeply divided nation.” That proved true following the election of the 577-seat National Assembly, in which Macron’s coalition failed to secure a majority, and Le Pen’s National Rally party secured 89 seats, making it the largest opposition party.

Swedish politics has moved to the right; the Sweden Democrats party, whose roots lie in neo-Naziism, won 20 percent of the vote in parliamentary elections last month. A Swedish writer notes how:

…the Swedish far right has profited from the country’s growing inequalities, fostering an obsession with crime and an antipathy to migrants. Its advance marks the end of Swedish exceptionalism, the idea that the country stood out both morally and materially.

Poland, like Hungary, has all the trappings of a democratic government in Europe, but these have been undermined by a right-wing government intent on creating a new Polish narrative. “To be truly Polish meant hating communists, devout Catholicism, and feeling nostalgic about the glories of Polish history,” one observes writes. Rewriting history has also meant denying Polish collaboration with the Nazis and ignoring rising anti-Semitism. But here again, Poland has diluted European anguish over its politics because of Poland’s acceptance of vast numbers of Ukrainians (roughly 2.5 million) since the war began and has been a faithful NATO ally in the face of Russian aggression.

Combating the Far Right

Is there a solution to the rise of neo-fascism? The remedy often proposed is to rely on and strengthen the institutions of democratic governance: civil society (independent unions, small businesses, NGOs), the judicial system, traditional political parties, and the independent media.

Hoping those institutions will stand up to authoritarianism is a thin reed on which to lean. For one thing, far-right rulers typically stack courts and the media with loyal people, eliminate the legal basis for NGOs to operate, and ensure that police and other security forces will crush any anti-regime organizing effort.

For another, democratic institutions are the primary targets of the far right, constantly under attack as “enemies of the people,” the causes of economic insecurity, and the “woke culture.” It’s not easy to defend against such mindless assaults, as we in the US know.

Third, liberals and progressives have their own criticisms regarding democracy. In the face of far-right attacks, the liberal left, not to mention the far left, can hardly defend corporate-dominated media, corrupt parties, courts that are blind to social inequities, and do-nothing legislatures.

Finally, the far right has proven far better than the pro-democracy forces at mobilizing capital, social media, and mutual support. For example, Europe’s far-right news outlets seem to follow a pattern that Orbán and his Fidesz party may have originated: He “set out to build himself a loyal media. Fidesz-affiliated oligarchs played a central role, buying out independent newspapers and private broadcasters. Today, Fidesz loyalists dominate the Hungarian media market.” Now, “alternative news” outlets are cropping up throughout Europe.

Put all these obstacles together with the near-universal economic upheavals, the war in Ukraine, and the ongoing pandemic. You have a recipe for democracy’s collapse and the triumph of neo-fascism.

There is, however, an on-the-other-hand: Latin America, where “since 2018, leftists have ridden an anti-incumbent wave into office in Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Chile, and Peru.”

And now, Brazil (if the polls are correct). Ask Lula (former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva) how it’s done, and he’ll tell you it was the same formula he has always used: firmly address poverty, the yawning rich-poor gap, and unemployment.

And then there’s always the possibility, now before us in Italy, that the far right will implode once in power. Silvio Berlusconi, the billionaire former prime minister and third wheel in the far-right triumvirate, seems still to have visions of grandeur and, worse yet, a fondness for Vladimir Putin. In contrast with Meloni, Berlusconi was revealed on tape to believe Putin was correct to attack Ukraine and was the victim of NATO’s rush to help Ukraine. There are no great leaders in Europe or the US, he went on; “the only real leader is me.”

One may hope such remarks will be the beginning of the end for Italy’s new leadership.

Mel Gurtov, syndicated by PeaceVoice, is a Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Portland State University and blogs at In the Human Interest.